Pentland Firth

Arielle Kommentare 4 Kommentare

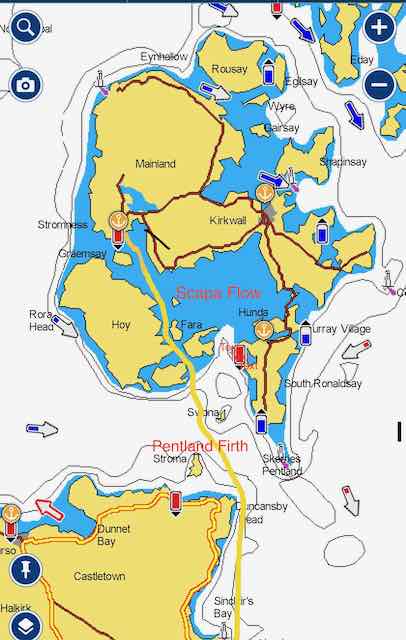

The rate of tidal streams in the notorious Pentland Firth is higher than that in any other part of the seas around Britain, especially at spring tide. We had waited for the currently exeptionally long and high spring tide to end. The pilot books and almanacs we consulted say, that passage should only be attempted in moderate winds and with a fair tide. The weather forecast predicted a fine breeze from west and we calculated 6 hours before HW Dover to be the right time to enter the sound between the Scapa islands. To make sure we made contact through Stromness Harbour with an experienced local sailor who affirmed our calculation.

The tidal streams through the Scapa Flow island of Flotta and South Walls run quite confused, so you will encounter sailing against the tide at some point. It is best to do this around slack water. Upon entering the Firth a still west-going tide perfectly set us off the island of Swona (at this point with the tide running east with full force a sailing vessel will helplessly be set onto its rocky coast). We reached mid channel with a now east-going tide, which carried us around Duncansby Head at a speed of 10 kts and more over ground. We had a fair crossing and an exhilarating sail. At 14:00 p.m. we reached Wick harbour on the Scottish mainland.

For the next day the crossing of Morry Firth lay ahead of us. Right in our way across to the Banffshire coast, in the middle of the Firth, lies a huge wind farm. It can be rounded east, which means having to reach far out to the North Sea, or by taking the longer route west of it. A glance at the wind predictions made us opt for the longer way, as gale force winds were blowing out there on the North Sea. We glided down the coast of Caithness, every once in a while being drenched by the Scottish rain. Rounding the wind farm our course turned south-east, which meant a downwind sail. The rising north-westerly wind was stirring up high seas. Wind from dead astern is never the most welcoming thing for a modern sailing boat and with these freakish waves Arielle rolled horribly and unpredicatably, threatening to gybe at any minute. The best we could make of it was sailing a course giving some slight bias sideways on the sails and hull and gybing controlled from time to time. We tore down toward this north-facing coast in seas breaking nastily, until we spotted Fraserburgh harbour, its mouth luckily facing east. We sped towards the harbour wall glad to find shelter behind its sturdy pier head.

Fraserburgh just like Wick is a vivid fishing harbour with the respectable grey town houses, so typical for this region. Fleets of working vessels are moored along the quai sides. Heaps of nets and lobster pots and the huge fish-packing stations speak of a still prosperous business. Fish is so asked for and the demand wants to be satified, but at the end of the day, it will lead to the death of the sea beds. Being on the spot, you see how people struggle for making their living and sustaining their families with this traditional trade – also powerful emotional arguments for it.

The next morning a north-westerly was still blowing hard. We decided to do some shopping and then headed for the seafront to have a look at the water. What we found was Fraserburgh Lighthouse Heritage Center. Led around by friendly guide, we were allowed to climb up to the top of the lighthouse. Here are some details of what we were told about the technology and about the life of the lighthouse keepers:

„The lighthouse of Fraserburg was built in 1823 by Robert Stevenson using the prism technology developed in the 18th century. It was at first operated with a petroleum lamp and later on with a mere 250 watt electric lightbulb. It could be seen from as far as 25 nm away, which improved the safety at sea considerably. The rotating prism gave the flash signal its destinctive sequence, which allows the mariner to identify it on his map. A lighthouse was maintained by three lighthouse keepers, working from sunset to sunrise in 4 hour shifts. They had to rewind the rotating mechanism every 30 minutes. They were working 6 weeks in a row and then had 2 weeks off duty. Every 4 to 5 years they were relocated to another lighthouse. The lighthouse of Fraserburgh was decommissioned in 1998, being replaced by an electronic lighthouse, which is maintained from a control center in Edinburgh.“

We owe much respect to these lighthouse keepers and their families, who often lived on remote headlands or uninhabitated islands and had to put up with a lonesome and unrewarding life.

By afternoon the wind had decreased and we could leave harbour. We were thankful for having found a safe haven among all the fishing vessels. It reminds us, that a lot of people are working hard to meet the growing demand for fresh fish, while we are playing around at sea with our boat. And we were thankful to the watchtower keeper, who kept us from going astray in this maze of harbour basins between huge concrete walls with very very narrow passages. He also asked for the number of crew onboard and for our destination, meaning that someone is keeping an eye on our safe journey.

4 Gedanken zu „Pentland Firth“

Wow, einfach traumhaft eure Tour, danke für die vielen schönen Bilder. Wünschen euch eine glückliche und sichere Heimreise.

Darf man britische Windparks nicht mehr durchqueren?

Hallo Frank, es ist tatsächlich verboten, sie werden auch bewacht und man wird über Funk angesprochen, wenn man sich zu sehr nähert. Wir würden es aber so oder so nicht in Erwägung ziehen, wir haben in Dänemark Segler beobachtet, die hindurchgehen. Mit besten Grüßen Barbara

Wouw, congrats for having been able to make it through this challenging waters! Great info around Robert Stevenson!